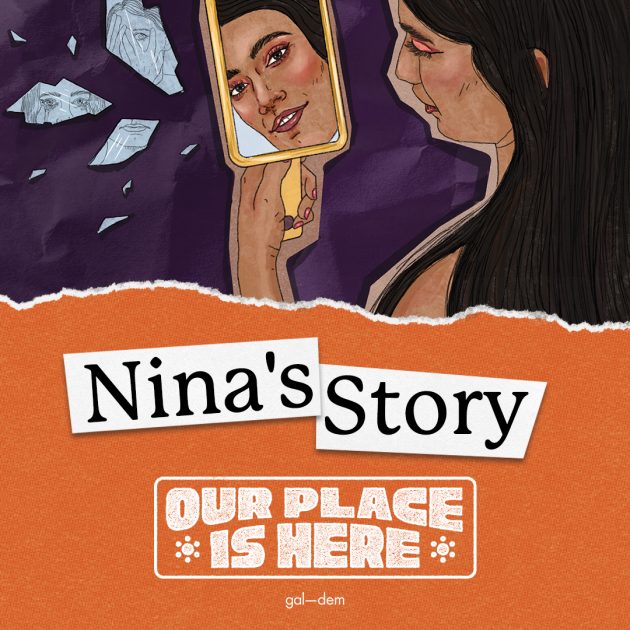

Facing the mirror: unpacking the personal and the political by Nina

Facing the mirror: unpacking the personal and the political by Nina

*This article was originally published on gal-dem in September 2022*

This essay is part of a collection of personal essays from gal-dem, written and spoken by migrant domestic workers living in the UK. These are their stories, in English and Filipino, written in their words.

My favourite place is in front of the mirror.

In front of the mirror, I see my history. My beauty. And all the places that mean so much to me. My hair, the lines on my face and the blush on my cheeks trace my journey from past to present. I recognise traumas confronted and unresolved. Combing through my hair, I hear a secondary school bully taunt me for being weird and different, for being feminine. As I follow the lines on my face, I walk through a stranger’s questions about my body, asking which parts I do and do not have. Through my make-up, I find the confidence to conjure up the person I feel I truly am.

In front of the mirror, I observe how other people have made me the receptacle of their own shame. Still, it’s also where I feel most present, where I feel truly ‘here’. I am ‘here’. But where is ‘here’ beyond the mirror? Who am I in a world that fails to recognise me, that refuses to see this person I see? How do I locate myself in the ‘here’ when nobody sees me?

“What is a passport but another nail driven into the coffin of oppression?”

Being trans and undocumented is a disconcertingly dangerous thing to be. The first time I went out looking for work as a housekeeper, a prospective employer asked me for identification documents. For most people, that would be as easy as making a cup of tea or getting dressed for bed. But, it is a lot more complicated for a trans woman with an irregular immigration status like me, who comes from a country that will never recognise my gender identity. I have no bank account. No driver’s licence. No utility bills in my name. All I have is a passport. But what is a passport but another nail driven into the coffin of oppression? I am trapped in this flimsy piece of paper that is meant to speak for me, to know me. A passport with a dead name. One that bears my likeness, but has never been me.

When I had my passport photo taken, I was told to tie my hair back. To not wear any make-up. To put on a shirt with a collar so stiff it felt like a guillotine. Not one piece of jewellery. Not even a smile. That photograph isn’t me; it’s a flawed, dehumanising system’s idea of me. Being asked for proof of identification is an exercise in re-traumatisation every single time.

I decided to avoid that prospective employer, but that wasn’t the last time it happened. It continues to happen. I have found some work now, fortunately, with people whose confidence in me as a capable housekeeper isn’t tied to an ID. Isn’t it ironic that the notorious serial killer Dennis Nilsen of Muswell Hill would have been hired immediately, just because he had a driver’s licence and a bank account?

“Why did he think he could violate my consent while still treating me with suspicion? Why does our society perceive domestic helpers as untrustworthy?”

What better illustrates this society’s distrust and disrespect of domestic workers than the idea that asking for ID is excusable because employers are letting a stranger into their homes and that their safety is compromised. Aren’t housekeepers going to a stranger’s house, too? Am I not also surrendering my fears for my own safety when I enter a prospective employer’s residence? I remember, one time, I was cleaning a bachelor’s flat while he was in his study working and chatting to friends on FaceTime. He suddenly appeared behind me, giving instructions. When I turned around to face him, he was holding his laptop with the camera facing my direction, making me visible to everyone he was speaking to. I felt violated, my privacy breached, my safety compromised. And that man and his friends probably found it humorous. Nowhere was there any consideration for my right to consent to being exposed in that manner, no apologies nor explanation given.

Why did he think he could violate my consent while still treating me with suspicion? Why does our society perceive domestic helpers as untrustworthy? Why does poverty and being a person of colour equate with duplicity? I am made to feel like an outsider in this country because of my skin colour and social status. Social and political stratifications like race and class shouldn’t have to exist. Why do rich, white people enjoy the benefit of the doubt? Waged domestic workers are here to do important work, work that allows a household to function, not to be someone’s slaves.

“In a transphobic, racist, misogynist, anti-immigrant society, where is ‘here’ for me?”

While most domestic workers are afforded a minimum wage, one’s immigration status can add other complications to their lives. Those with irregular statuses like me are often given wages below the legislated minimum, with employers citing their status as a reason. I am lucky to not have had that experience but I am more the exception than the rule. A vast majority – if not all domestic workers – are women of colour and the plight of domestic workers is only indicative of how society in general views the socio-political category that is ‘woman’.

In a transphobic, racist, misogynist, anti-immigrant society, where is ‘here’ for me? I think the better question is: do I want to be ‘here’? To be a part of this society’s current iteration? Can I choose otherwise? Because I would like to. I would like, instead, to help build a society where everyone can be present anywhere, anytime and not just in the ‘here’. A world where we won’t need mirrors to help us locate ourselves and reflect our truths, privately, in our own locked off selves. Instead, we would exist in a world where we can see ourselves reflected in the light of our shared humanity, where we can be seen in the image of other members of our community and in the world at large.